By Chet Babla, SVP, Strategic Marketing at indie

The National Highway Transport Safety Administration’s (NHTSA) Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standard (FMVSS) No. 127 in the U.S. mandates Automatic Emergency Braking (AEB) and Pedestrian Automatic Emergency Braking (PAEB) – including, for the first time anywhere globally, nighttime scenarios – in all new passenger vehicles by September 2029, presenting both a challenge and an opportunity for automakers. The standard states that vehicles will need an AEB system and Forward Collision Warning (FCW) that operates at forward speeds above 10 km/h (6 mph) and below 145 km/h (90 mph).

Traditional front camera systems that underpin some of today’s AEB and FCW automated Advanced Driver-Assistance Systems (ADAS) technologies will be challenged by the new FMVSS mandate, in particular the nighttime requirement. Fortunately, advanced infrared (IR) camera sensing leveraging next-generation Image Signal Processors (ISPs), and complemented by long range radar, shows great promise in meeting the proposed regulations. This article explores how camera- and radar-based sensor innovation will support automakers to meet FMVSS 127 requirements, enhancing pedestrian safety and paving the way for more reliable and robust automated driving systems. With a portfolio of class-leading sensing and processing technologies, indie is positioned to drive innovation in automotive safety and perception.

The FMVSS 127 Challenge and Opportunity

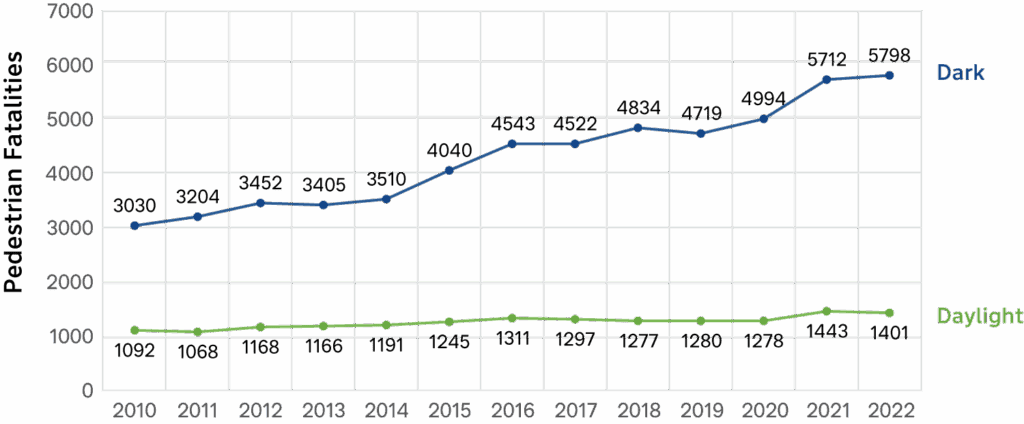

In its report, ‘Pedestrian Traffic Fatalities by State: 2023 Preliminary Data (January-December)’, the Governors Highway Safety Association (GHSA) estimated that in the U.S., 7,318 pedestrians were killed in traffic accidents in that year. The figure represented a 5.4% decrease in deaths from 2022, but a 14.1% increase in deaths reported in 2019. There has also been a consistent pattern, over many years, showing pedestrian deaths occur almost as much as three times at night, from those that occur in the daytime (77.7% of accidents in 2022 occurred during night hours), highlighting the significant need for nighttime detection capabilities.

Pedestrian deaths 2010 to 2022 (Data source: GHSA)

In the most recent findings from the GHSA, published March 5, 2025, 3,304 pedestrians were killed in the U.S. during the first half of 2024. That’s 2.6% lower than in 2023, but still up a staggering 48% from a decade earlier.

NHTSA’s FMVSS No. 127 regulations are a legislative response to these tragic statistics and mandate the inclusion of AEB and PAEB systems with nighttime capabilities to be standard in all passenger cars and light trucks by the 2029 deadline.

The mandate for AEB systems to operate effectively in all weather conditions, and crucially including nighttime, requires advances in sensor technologies, processing, and perception. Some organizations, such as The Alliance for Automotive Innovation, have raised concerns with NHTSA about achieving FMVSS 127 in a reasonable timeframe due to the technical challenges. But ultimately, this regulation serves as a catalyst for automotive sensor technology innovation and will represent a critical step towards improving safety standards.

Sensor Capabilities

Camera and radar sensors are ubiquitous in today’s vehicles enabling regulatory mandated safety functions, new car assessment program (NCAP) driver safety features and driving convenience capabilities. But while Toyota first deployed a camera in a production vehicle for backup monitoring as early as 1991, cameras were not deployed for safety applications, such as collision avoidance, until the early 2000s, leading to mainstream adoption in the 2010s. Similarly, radar saw initial use in trucks and premium vehicles for adaptive cruise control (ACC) applications in the late 1990s, but with the first deployment of automatic braking not coming until 2003 when Honda introduced its Collision Mitigation Braking System, quickly followed by other mainstream carmakers.

Camera-based sensing supports safety capabilities such as AEB, blind spot detection (BSD), and lane departure warning, and convenience features such as ACC and parking assistance. Camera sensing solutions must feature multiple attributes to meet the needs of these automotive applications. Perhaps surprisingly, however, visible light cameras do not need to be particularly high resolution to operate effectively for front sensing, and around two megapixels is a common resolution deployed today. High dynamic range (HDR), however, is an important capability to address cases where the sensor must avoid becoming overwhelmed by bright light, while also preserving the darker regions of a scene; this could occur in a parking garage, or when the sun is low in the sky, for example. Additionally, support is critical for the newest sensor color filter arrays (CFAs) to enable operation in lower lighting conditions while simultaneously maintaining the highest accuracy color reproduction to ensure automation and safety systems can correctly discern, for example, red and amber traffic signals. Low latency image signal processing is also a key requirement for downstream perception processing and real-time safety system actuation.

Of course, in poor lighting or at nighttime, visible light cameras, even with the latest CFAs, will be ineffective, and infrared (IR) cameras, sometimes called thermal cameras, which measure the thermal energy emitted by objects, must be used. These cameras perform particularly well in low light and adverse weather conditions, and for automotive long range detection applications, sensors operating in the 8-14µm long-wave IR band are typically used.

Radar sensing complements visible light and IR camera systems. It is excellent for detecting distance to objects and their direction and velocity, even in adverse weather or complete darkness. Radar, typically operating at 77 GHz and using frequency modulated continuous wave (FMCW), is widely available in mass-market vehicles today supporting AEB, BSD and cross-traffic alert safety systems, and ACC and parking convenience features. However, radar has traditionally struggled with precise object detection and classification. For example, many deployed radar solutions today cannot reliably distinguish between pedestrians and other objects at distance. False positives in PAEB situations are one consequence of this, so braking may be applied when it’s not needed, or conversely the pedestrian may not be detected at all and emergency braking not applied.

However, there has been significant progress recently to improve the resolution capabilities of radar through the deployment of multiple physical channels, and more scalably, MIMO (multiple-input-multiple-output) transmit and receive antennas to create a larger virtual antenna array. By combining this improved hardware system with advanced software algorithms, the latest generation automotive radars can deliver higher effective angular resolution and improved detection and classification. These newer higher resolution systems are sometimes referred to as 4D radar, or imaging radar, and in addition to improved detection of distance, speed and direction of an object, also provide elevation information about a vehicle’s environment.

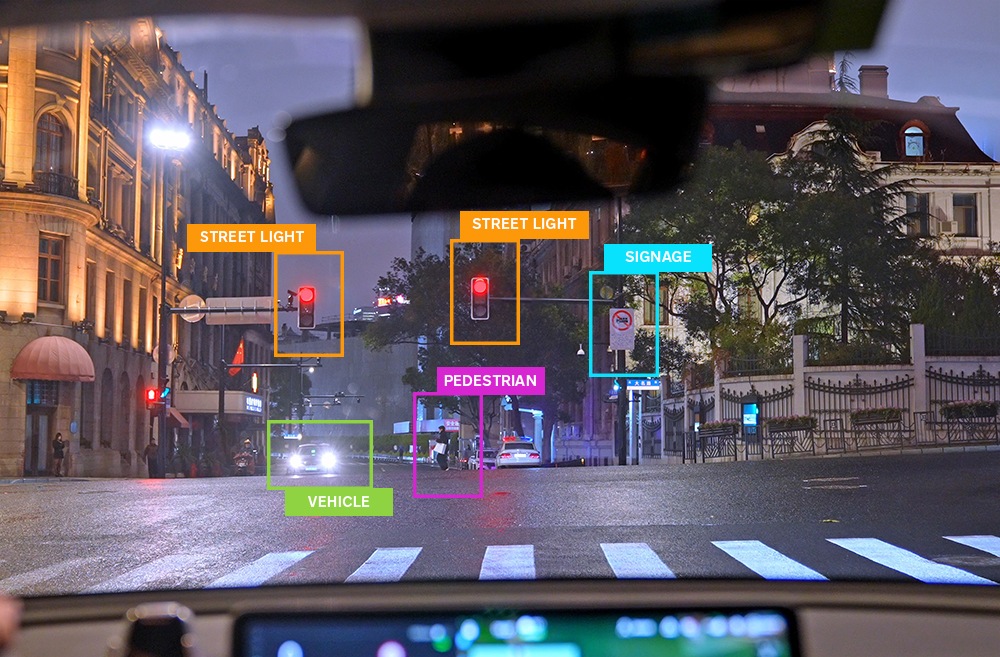

Since radar has limited object classification, for instance it cannot discern a red traffic light from an amber light or interpret road signs, and cameras can be thwarted in poor lighting or adverse weather while also have limited distance sensing capability, the complementary combination of these sensors – i.e. sensor fusion – provides a greater sum-of-the-parts solution for ADAS sensing, including FMVSS 127’s nighttime PAEB.

Moving towards sensor fusion

By combining the rich semantic capabilities of cameras with the superior range and velocity performance of radar, the overall detection accuracy and reliability of ADAS sensing – particularly in adverse environmental and lighting conditions – can be enhanced, addressing the weaknesses of the individual sensor types.

One such approach to fusion is decision-level fusion (also called “late fusion”). In this approach, the output of the vision system is a set of bounding boxes with associated confidence scores indicating the likelihood of a pedestrian or vehicle, for example, being present. The output of the radar sensor is a 2D point cloud, with points clustered based upon position, velocity, and intensity, and heuristically labelled in binary as potential objects (1 for candidate object, 0 for not). The radar clusters are mapped into the camera’s reference frame and transformed into the image plane to align with the vision bounding boxes. Extrinsic radar-to-camera calibration is critical for accurate alignment. This data is then processed by a fusion algorithm, for example, the Dempster-Shafer method. It is important to note that in this approach, the vision detection provides the primary confidence score for each bounding box, and the radar clusters within the bounding box region providing a supplementary fused confirmation. If the algorithm’s fused confidence exceeds a pre-determined threshold level (say 85%), the detection is considered robust and reliable.

An example approach for radar-vision fusion

In this fusion setup, the radar serves to strengthen or weaken the confidence of the vision-based detections, especially under low-light or ambiguous conditions as envisaged under FMVSS 127’s nighttime PAEB. Similarly, false positives from the vision sensor can be suppressed if not corroborated by the radar, while conversely, low confidence – but true – vision positives can be promoted.

Beyond FMVSS No. 127

The global imperative to reduce both vulnerable road user injuries and fatalities will continue to drive legislative demands such as FMVSS 127, and, as a result, technical innovation. No single sensor technology will deliver the necessary performance and resilience, and the industry must explore the best combination and approaches of sensor technologies and fusion approaches to achieve these at a viable cost. Ultimately, semiconductor companies with expertise across the spectrum of candidate hardware and software technologies will be best placed to support the automotive industry’s ambition to save lives.

Learn more

To learn more about indie’s solutions supporting driver safety and automation, please visit: